The Battle of Stalingrad (July 17, 1942-February 2, 1943)

Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia by the Germans, began on June 22, 1941, with a sweeping onslaught over the Russian border, using 150 divisions (three million German soldiers). In the first month, the Germans covered between 200 to 400 miles, and then began the three-prong division of forces. One section headed northeast to Leningrad, commanded by Field Marshall Wilhelm von Leeb; the central part moved towards Moscow, commanded by Field Marshall Fedor von Bock; and the third part headed southeast, first to Kiev, then Rostov, close to Stalingrad, commanded by Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt. Unfortunately for the German command, Adolf Hitler then decided he wanted to split up groups to reinforce the drive, both north and south, instead of moving decisively straight to Moscow. It was during this delayed time of bickering between generals and Hitler about the best direction to advance, that the Russians began to regroup and fortify towns in preparation for fighting back.

Division of Forces

German Field Marshall Rundstedt had initially taken Kiev before the stalemate at the German Command offices. Then he took Rostov, but due to bad weather, could not hold it, so lost it again. Once the summer weather came in, the Germans pushed back, re-taking Rostov, and then Sevastopol, Novorossisk, and finally, the oil fields of Maikop. When the German forces took Sevastopol, the German army was split into two groups, with Group B heading north towards Stalingrad, commanded by General Friedrich Paulus, while Group A headed towards Maikop. On August 23, 1942, the first arrival of Group B, one panzer division and the 3rd Motorized Division, arrived at the northern and southern outskirts of Stalingrad, and waited on the edge of the Volga River for the rest of the forces to pull up.

The Battle Begins

Early on, there was very little resistance, and a massive bombing raid was conducted first, reducing much of Stalingrad into rubble. The Sixth German Army under Paulus, formed of five army corps, 13 infantries, three panzers, three motorized divisions, and one antiaircraft division, began moving into the city. However, the rubble and multitude of dead bodies in the streets, created numerous obstructions in moving forward quickly. As the Germans moved slowly through the city, with Hitler badgering Paulus to make a quick end of things, Russian command was sending in more soldiers. With German forces fully committed inside the city, the battle became bloody, with desperate Russian soldiers and armed civilians fighting hand-to-hand combat with equally desperate German soldiers.

General V.I. Chuikov oversaw the Russian 62nd Army, which was defending the city, while Marshal Georgii K. Zhukov planned a counteroffensive from outside the city. In November 1942, Zhukov surrounded Stalingrad in the event known as Operation Uranus, using six armies of one million soldiers, while Hitler demanded his soldiers stay and fight, with no thought of retreat or surrender. A rescue attempt was made for the German soldiers in Stalingrad, by the 57th Panzer division under General Hermann Hoth, but it only got as far as the Askay River, before it was taken completely out.

Hitler promoted General Paulus to Field Marshall on January 30th, but Paulus, who was captured by the Russians along with his staff on January 31st, and realizing that there was no hope for supplies and reinforcements, surrendered his 91,000 remaining soldiers on February 2, 1943.

The ramifications from this battle was that the Germans suffered a serious defeat, and it was a turning point in World War II, where it was seen that Germany could be defeated. Part of the problem was Hitler’s inability to strategize properly, including understanding the weather problems, and how delays would change the battle plan layout.

It is also said that Hitler wanted Stalingrad destroyed because it carried the name of Russia’s leader, while Stalin refused to give up Stalingrad for the very same reason. With this massive loss of German soldiers, it also weakened Germany to a point, that when the Russians invaded Germany, there were not enough German forces to stave off the attack effectively.

The number of German dead soldiers was about 150,000 picked up from the field, while nearly 100,000 Russian soldiers and civilians died in the battle at Stalingrad.

###

| The Germans | The Russians |

|

|

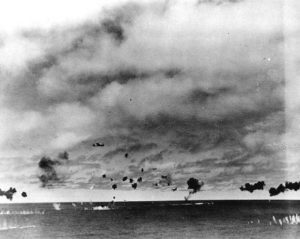

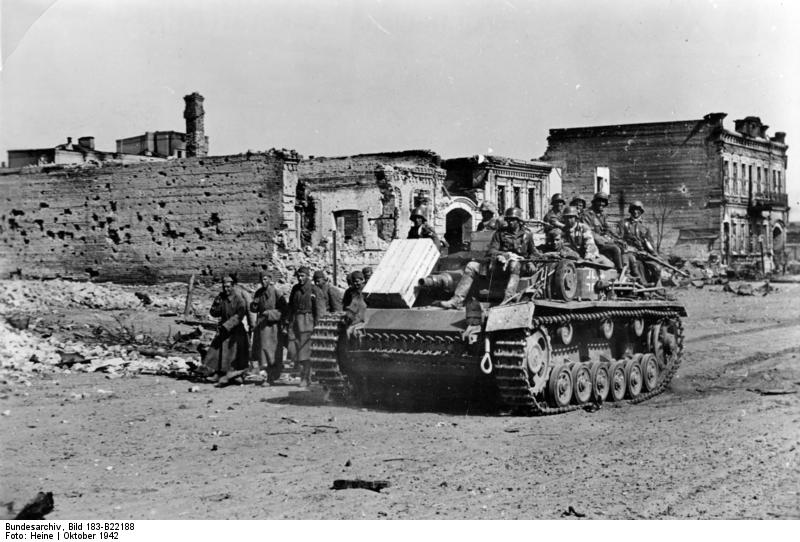

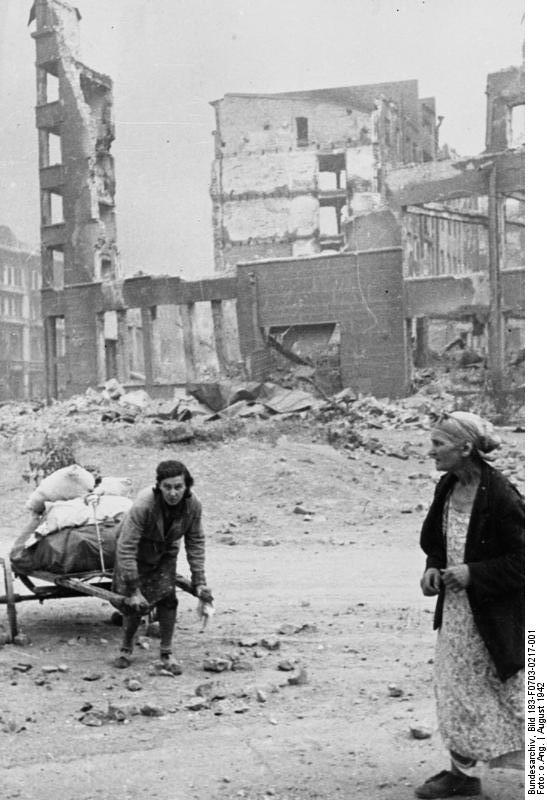

Photo Gallery

Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber over Stalingrad, September 1942

Photographer:Klose

Source: German Federal Archive

German soldiers riding on a StuG lll assault gun, October 1942

Photographer: Heine

Source:German Federal Archive

A wrecked Soviet T-34 medium tank October 8 1942

Photographer: Herber

Source: German Federal Archive

Soviet soldiers fighting in the ruins of Stalingrad, late 1942 or early 1943

Source: German Federal Archive

Two Russian women in the ruins of Stalingrad, August 1942

Photographer: Jakov Rjumkin

Source: German Federal Archive

Russian infantry firing their weapons from a rooftop in Stalingrad February 2 1943

Source: German Federal Archive

Soviet soldier advancing in 1943

Photographer: Georgi Zelma

Source: Russian International News Agency

Soviet Soldier waving a red flag as a sign of victory at a building near the central square, January or February 1943

Photographer: Georgi Zelma

Source: German Federal Archive